How are Japanese Universities Approaching Assessment?

Translation : Hamana Atushi (2018). Meeting the Challenges of Learning Outcomes-based Education. Toshindo: Tokyo. Chapter 1, Section 2

How are Japanese Universities Approaching Assessment?

What exactly is happening with assessment in Japanese universities? According to a survey conducted by the Private University Higher Education Research Institute (itself an arm of the Japanese Private University Association), of the 773 academic department heads polled in August 2011, about 80.8% indicated that their department courses listed learning outcomes on their syllabi. Thus it appears as though some universities are attempting at some level to indicate course objectives and broader assessment goals to students.

However, the actual number of departments that have "all courses" returning graded tests and reports to students is only 2.1%. The number that responded that "a large numbers of courses" returned graded work was only 11.7%, while the number that responded that "about half of courses" returned such work was only 17.1%. In other words, almost 70% of university (programs) do not return their course work. As a result, students in these departments do not know why they received a "excellent" (or "A") grade or a lower grade, because there is no indication of the actual contents of their course assessment.

<graph 1-3>-

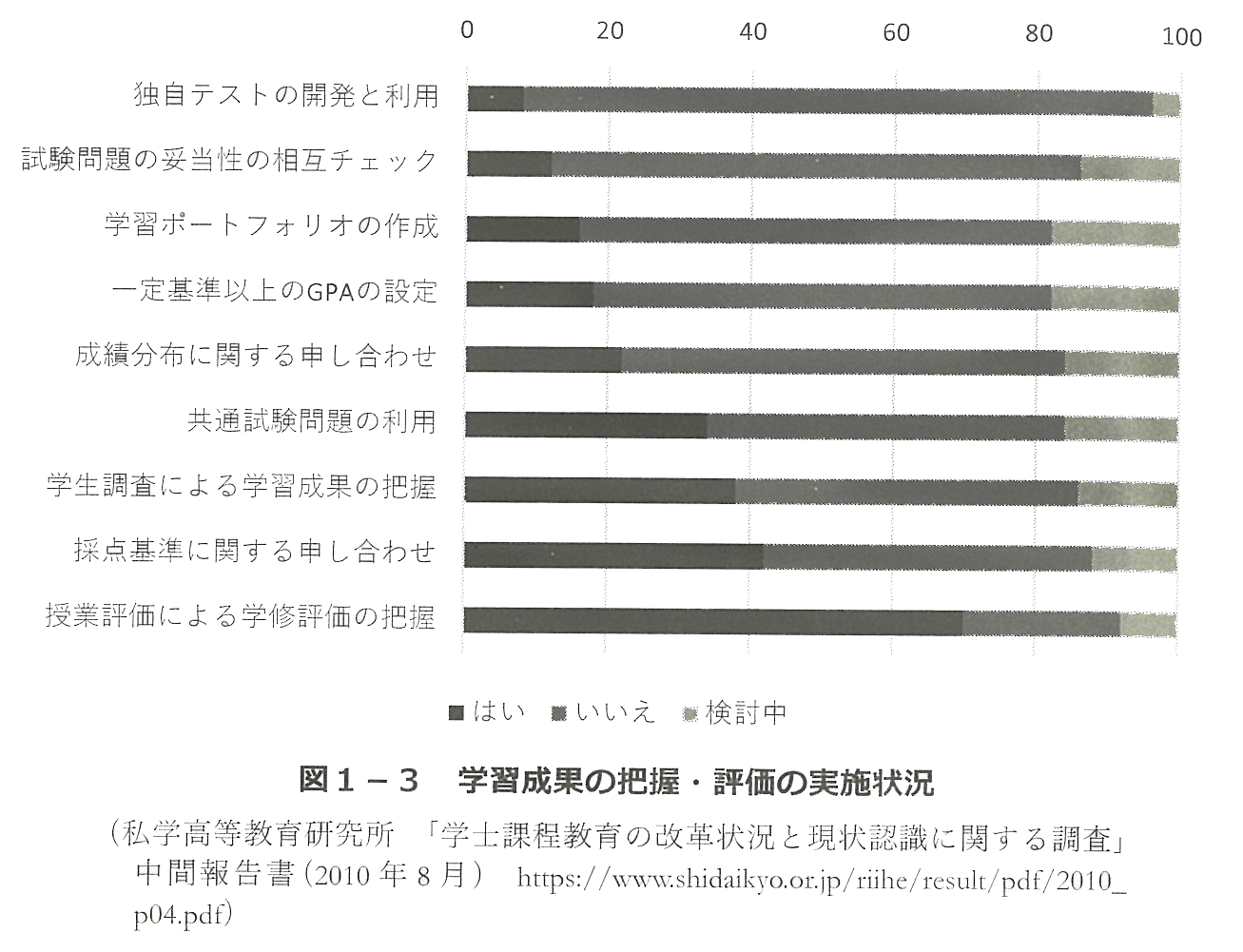

Additionally, the number of universities that conduct coordinated, rubricked, and systematic graded assessment are small in number. Although 34.3% of departments indicated that instructors teaching the same course might share some common exam problems with each other, the number of instructors that coordinate their grade distribution was only 22.4%, and only 25.5% coordinated multiple graded assessments together. In other words, graded assessment coordination only took place in slightly over 20% of instances. Instances where institutions tried to create and use commonly developed objective tests were only found 7.8% of the time, whereas the cases where departments checked the suitability of test problems across courses was found in 11.4% or about tenth of all programs.

(See graph 1-3)

Similarly, although subjective student evaluations such as student course evaluations(69.9%) and surveys of current and former students (45.7%) indicated a relatively high number of students who indicated that they achieved learning outcomes set-out by the course, the actual number of students who could actually document such learning outcomes (through such things as a learning portfolio) were only 13.7%. In other words, the actually reality of Japanese universities being able to meet society's demands to make learning outcomes visible still remains a distant aspiration.

The Basis and Standards of Assessment

The basis of assessment can be thought of as meeting three important criteria:

- Is what it is trying to explain/evaluate appropriate?

- Is it something that can be verified by a 3rd party?

- Is what is being evaluated in a institution or program representative?

These three conditions are essential to conducting assessment. This can be achieved directly though the evaluation of well-established tests and exams, graduation thesis or research, evaluation of performance by experts, the sampling of course assignments and work, etc. Assessment can also be achieved indirectly though well-grounded learning portfolios, evaluations by graduates and employers, self-evaluations by students at the time of graduation, or surveys of student learning behaviors, etc. Regardless, be it through direct or indirect methods, it is necessary to assess in a multi-faceted and comprehensive way. In Japan, assessment has up until now been conducted in ways that greatly value quantitative measures such as test scores, GPA, graduation rates or entrance exam distribution scores. However, relying on such methods exclusively is no longer enough.

-

For qualitative approaches for assessment, the use of criterion-based rubrics is effective. In the U.S., for example, the AAC&U (Association of American Colleges and Universities) has tried to facilitate the assessment of liberal education in the 21st century through LEAP (Liberal Education and America's Promise) initiative, specifically though the widely used VALUE (Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education) rubrics. Through widely available learning objective-based charts, institutions can measure and assess student learning growth based on specific achievement criteria. This is a particularly suitable way to qualitatively assess learning using achievement and performance-based references. Moreover, with just a little practice, university instructors can effectively learn to apply the rubric instrument in ways that are normed and consistent with minimal individual difference between assessors.

If rubrics designed to assess learning are shared among university instructors, it is then possible to commonly evaluate at the institutional, faculty and department level. Through the consistent, systematic application of vertical, criterion-referenced assessment dimensions and horizontal criterion-referenced assessment levels, students can begin to understand the extent their course learning is meeting its achievement goals across their four-year program. Also, because rubric-based assessments are able to reduce discrepancies in grading between faculty members, it is also possible in the future to increasingly have them give comments on common reports and portfolio items of students, as well as measure learning across many different dimensions.

How Should We Go about Building an Assessment Policy?

In order to conduct assessment, it is first necessary to make the learning/course objectives clear. Along with the commonly shared goal-setting criteria found in Japanese universities' "Diploma Policy" and "Curriculum Policy," it would also be equally easy for institutions to also share with students, faculty and society a policy for assessment. It could first include examples found in school diploma policies as academic skills, professional skills, general competencies and other abilities.

More than that however, it would also demand a blueprint that would make clear the kind of learning growth that could be experienced by students upon entering the institution. It would also be necessary to measure the changes in student learning through a combination of multiple assessment methods and measures during different times over the course of an undergraduate program.

-

If one thoroughly implements a longitudinal assessment policy focused on the individual growth of students, the feedback in courses on student outputs and exam performance becomes ever more important. It is more important to return student work with comments and grades. The full realization of assessment therefore means that a student's growth and achievement is visible and understandable to themselves. Implemented assessment that is measurable and visible is therefore very valuable to students. When combined with learning portfolios, one can trace longitudinal change on an individual student level as well as grasp the overall growth process of the cohort as a whole. However, such a system requires much energy for the university, faculty and students to carry out.

An assessment policy will differ depending on the organization as well as target (be it at the individual student, course or instructor level, etc) of evaluation. Nonetheless, within the larger context of a diploma policy for an undergraduate degree, it can become an important means to systematically implement an education plan that interrelates different courses together as well as making clear to faculty which individual courses will be responsible for developing which students skills and capacities.